The kids who ran away to 1960s San Francisco

I followed my curiosity and ended up at the library reading hundreds of letters of runaway teenagers who came to hippie San Francisco

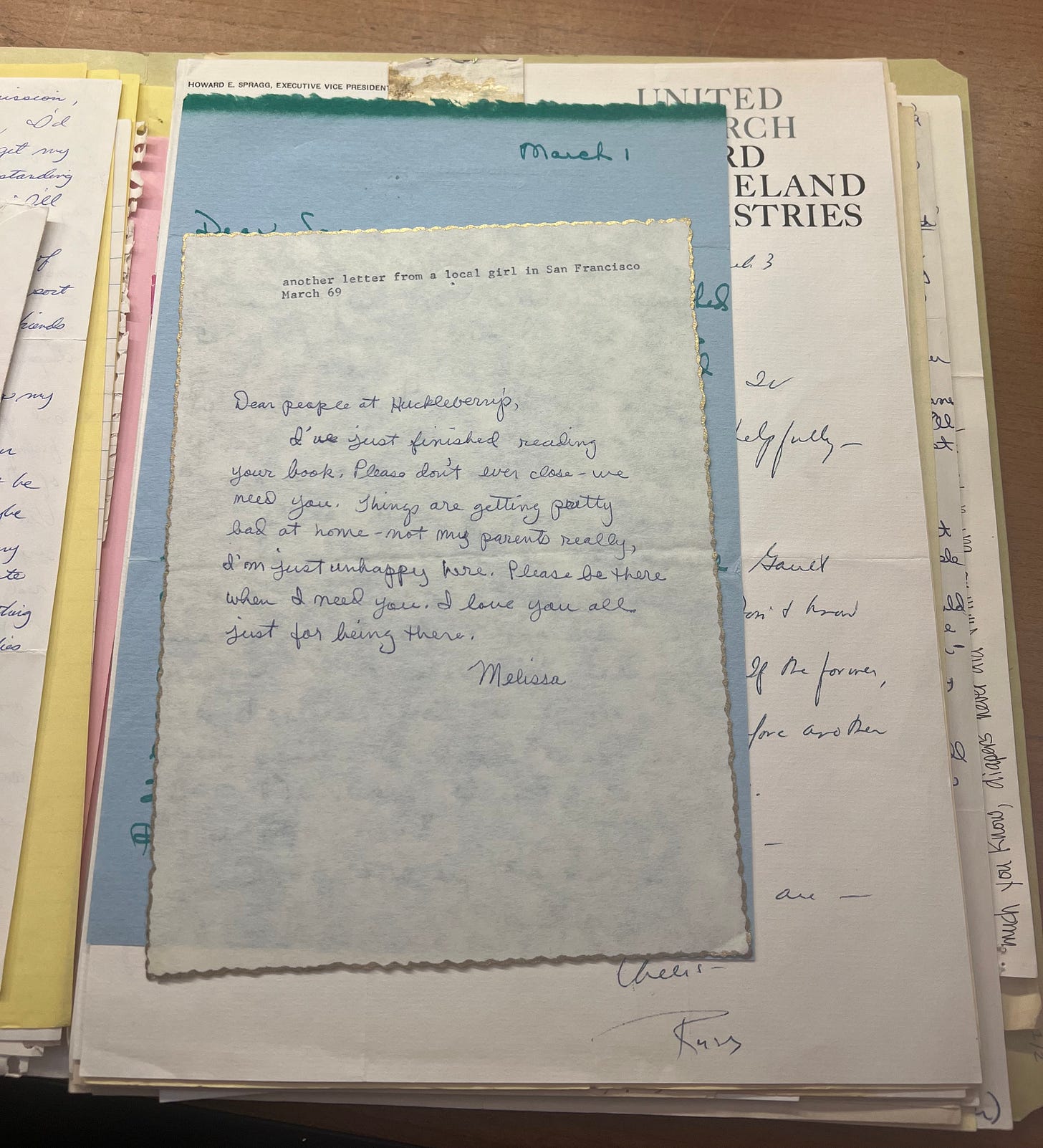

“Dear people at Huckleberry’s… Please don’t ever close – we need you… I love you all for just being there. Melissa” March 1969

I’ve been reading Season of the Witch, a fantastic book on the history of San Francisco from the 1960s through the 80s. Somewhere in the middle, there’s a chapter on Huckleberry House, a home for runaways started in the late 60s. It was just a couple pages, but it stuck with me.

There was something about the story of the founder, a reverend turned hippie, who decided to help teens when everyone else had given up on them. It resonated with my own life story and motivations for building Nautilus, my non-profit.

Of course, my first instinct was to look the house up, hoping to answer my many questions:

Who were these kids?

What was it like to live in this house, in this era?

Who was the founder – is he still around?

Is the house open to this day?

While skimming through the house’s Wikipedia page, I discovered that archives on its history were available at the main library of San Francisco, including:

The ACTUAL letters exchanged between teen runaways and the house’s founder during the 60s!

I can’t explain the rush of adrenaline that gave me.

At that point, it felt like I had two options: either I was going to impulsively go to the library that very same day and get to the bottom of my curiosity, or I would forget about it and move on.

Like many of us, I’m busy, so my mind started to come up with all the reasons not to go. Waste of time. I got meetings. Very unproductive way to spend a Tuesday. Seriously, like, what’s even the point?

Luckily, I was able to break through this stream of thought and realize that I aspire to be a high agency individual who is free to follow her curiosity.

So, just like that, I went.

It was my first time at the San Francisco Public library. Most people there seemed to be using the building for everything but reading: charging their phone, using the restroom, or just resting from the chaos of the streets. I headed to the 6th floor where the special collection is located.

When the staff looked up Huckleberry house, they didn’t just find a few documents, but actual boxes, including photos, too.

The boxes were in an off-site storage, so I had to place an order. It felt oddly formal for such an impulsive curiosity. Fill out a form. Leave my name. Wait 10 days for the boxes to be shipped to the library. By then the side quest had become too meaningful to back out of, so I just went with it.

Ten days later, I was back on the sixth floor. The special collection section is a big room, but I was alone with the staff for most of the afternoon. They kept my ID and my belongings in a locker, and gave me gloves to handle the photographs. There was something ritualistic about the whole process.

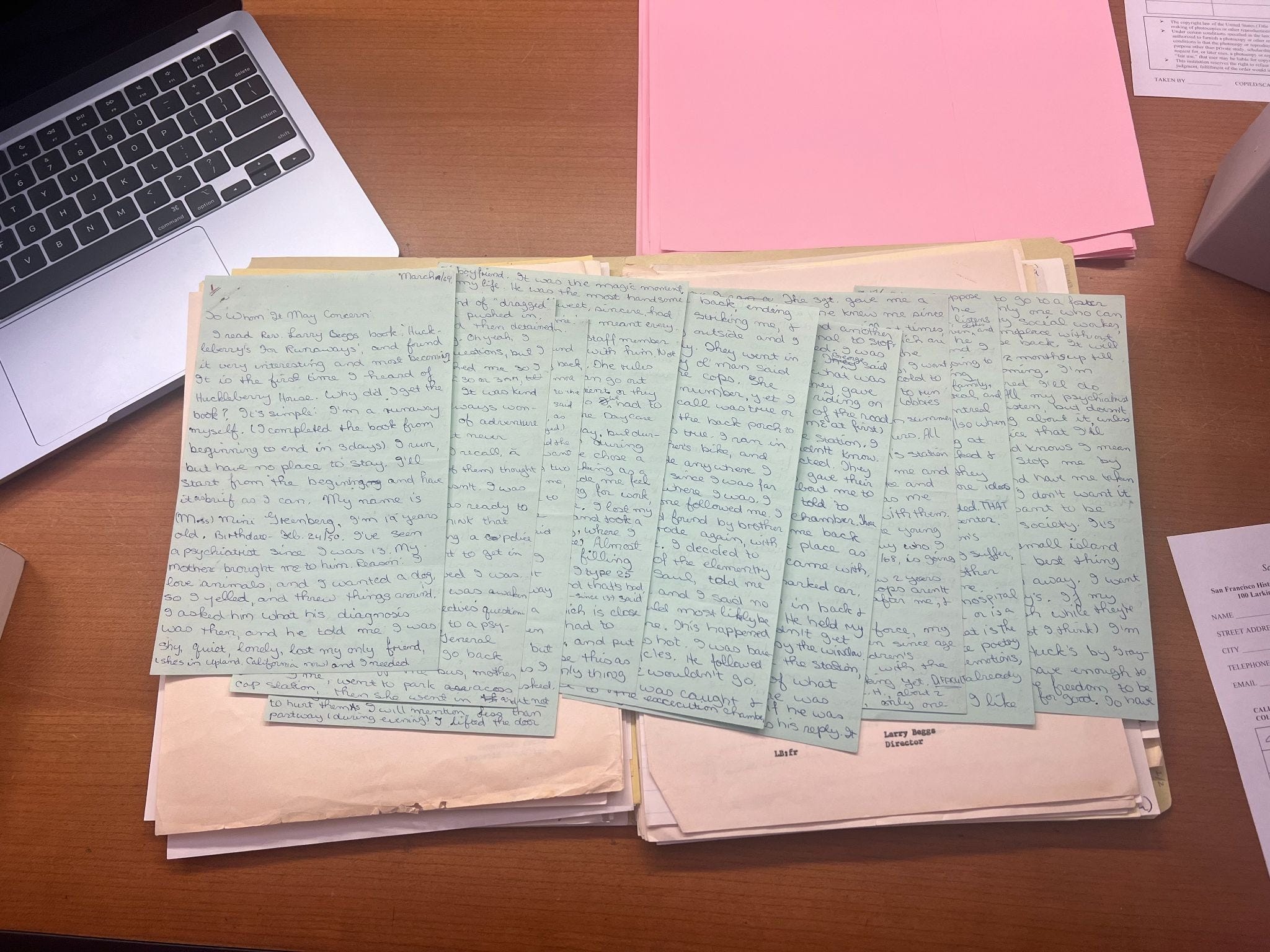

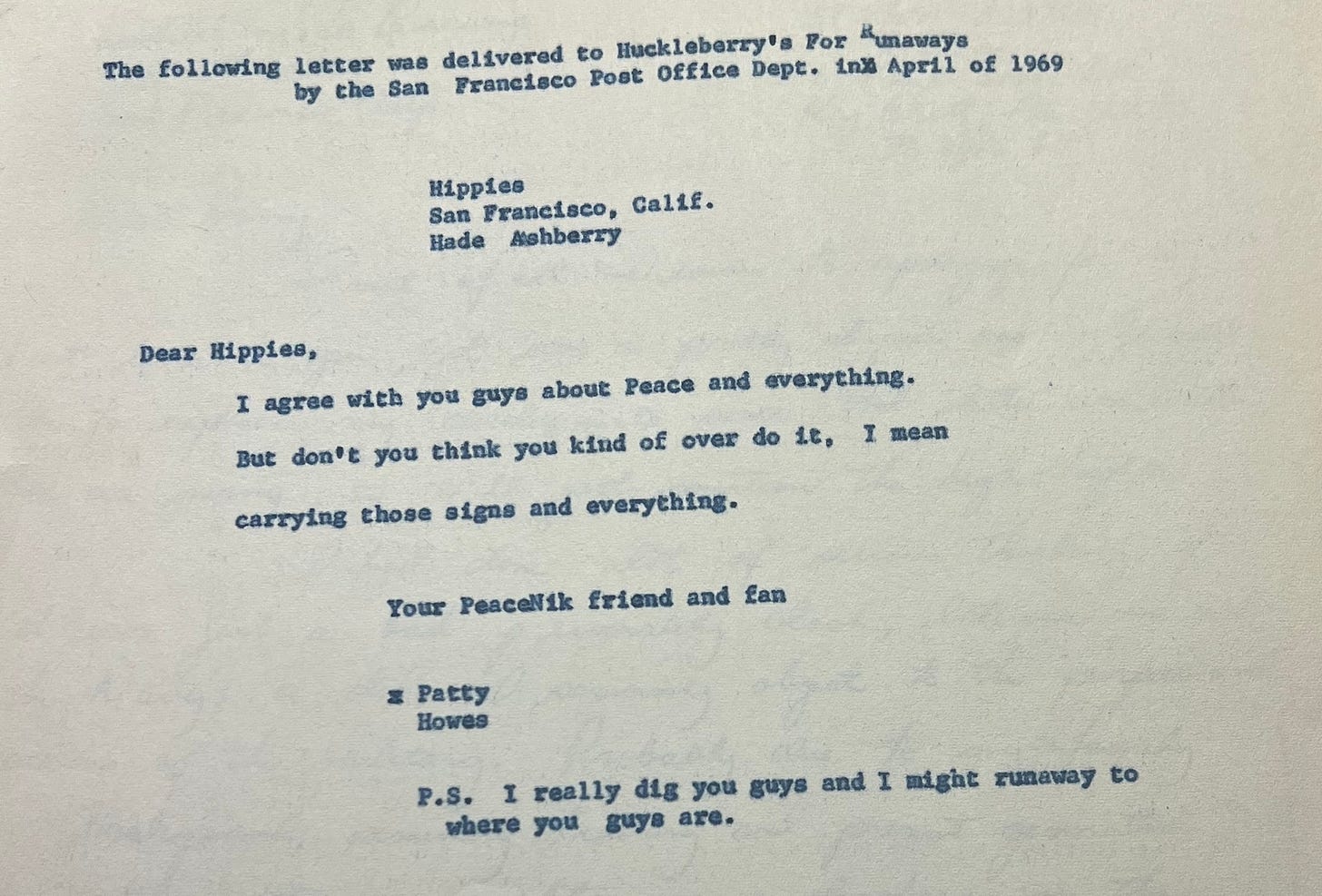

I opened the first box: letters. Hundreds of them.

These were handwritten letters from teenagers addressed to Larry Beggs, the founder and director of Huckleberry house. I was struck by how long some of these were. Literally pages and pages of stories and difficulties these teens were going through back home, their desire to run away, and questions about the Huckleberry house.

I also found copies of the replies to these letters. Larry’s letters are written carefully, and you can feel that he takes those teens seriously. When teens write about suicidal thoughts, he doesn’t jump into advice or pretend to know their life better than they do. He often says some version of: I don’t have enough context to tell you what to do. But I’m listening. I care that you exist.

Reading through these letters got me thinking about what the lives of these people ended up looking like. Most of the correspondence was exchanged between 1967 and 1969. And here I was, 50-plus years later, holding pieces of paper on which they poured their heart out of desperation.

The librarians assumed I was working on some kind of academic project. At one point, one of them asked me what my research was for and which university I was at. The funny thing is, I am a high school dropout – And I had no reason to be here other than pure vibes.

Later that afternoon, I started talking to the photography curator. I told her I found my way there through the book Season of the Witch. She smiled and told me that David Talbot, the author, had spent weeks in that exact same room, looking at the same documents, helped by the same staff.

There was something touching about that too: the idea that a book sends you to the archives, and that you end up literally tracing the author’s footsteps.

By the time I left, it felt like I had stepped into a time travel machine that sent me into a parallel San Francisco. But there was also a strange continuity with the city I moved to in 2025:

Today, young builders from all over the world cold-email successful tech founders, trying to make their way to San Francisco to build the future. Back then, teens wrote these long letters to Rev. Beggs, someone they similarly looked up to, and also hoping to make their way to San Francisco for a different future.

If there is a lesson to this side quest, it’s certainly this: you can JUST go to the library (or do things, in general). The world is full of rooms like that sixth-floor reading room, and it’s up to you to walk into them. Work usually can wait, and you often come back more inspired to it when you’ve given yourself permission to wander.

Just go on that quest!

Yes, Huckleberry house is still around and with the same mission. If you want to donate to support at-risk teens who find refuge there, you can do so here.

If you want to donate or collaborate on Nautilus, the non-profit I founded that welcomes young artists, scientists and founders to SF and help them do work that shapes the future, get in touch at zeldapoem@gmail.com

I made the journey to San Francisco in 1968. I'm now retired and writing about the Summer of Love in New York. I'll be in touch with you.

Thank you to Zelda for writing this, and to Ted Gioia for signposting it!

I wonder what happened to those children...